Conservative Christchurch or the City of Controversies?

Content warning: Mentions of racial and homophobic events, as well as offensive language in the form of slurs.

Source: Christchurch City Council Newsline, from the Springbok tour protestors in 1981.

When thinking about the most conservative cities in Aotearoa, Ōtautahi Christchurch typically springs to mind. There is a widely known stereotype in New Zealand that Christchurch is one of our more conservative cities, alongside the idea that the further south you go, the worse it gets.

Canta wanted to delve deeper into the discussion to try and navigate the current state of racist and homophobic ideologies right here in Christchurch.

Through the history books:

In a Canta survey, most respondents described Ōtautahi as conservative, often sharing rather unpleasant anecdotes to support their views.

But has it always been this way? According to University of Canterbury history lecturer Geoff Rice, "Christchurch has not historically been known as a conservative city."

"Since the 1890s, Christchurch was home to the women’s suffrage movement and the temperance movement," Rice said.

These were radical and progressive movements for their time, firmly establishing Christchurch as a city of change rather than conservatism.

In a document titled Christchurch City Contextual History Overview, published by the Christchurch City Council, these movements are discussed in detail.

The Women’s Christian Temperance Union, founded in Christchurch in 1885, aimed to address abuse of alcohol. This organisation became a driving force behind women’s suffrage campaigns, later gaining national prominence under the leadership of Kate Sheppard in 1896.

"[Christchurch] has been a predominantly left-wing and Labour-voting city since the 1930s," Rice noted.

This trend continues today, with Labour MPs representing Christchurch East, Christchurch Central, and Wigram. Even in Banks Peninsula, the Labour candidate only narrowly lost to the National candidate by a margin of about 400 votes.

So, if Ōtautahi has such a progressive past, why does it carry the label of a conservative city?

Rice offered an intriguing perspective: "Rather than conservative, it would be better labelled the city of controversies, as major issues seem to divide the city into opposing camps."

A respondent to our survey pointed to schools and suburbs as significant factors contributing to the conservative Christchurch image. They shared personal experiences, acknowledging that schools are a big thing down here.

*Emma said: “I have been to job interviews where I’ve been asked about it. I've been offered and prevented from opportunities because of it, and it is crucial that you go to a 'good high school.'"

*Emma also highlighted the stark wealth divide in Christchurch, noting, "suburb status is also another big one. I've visited lots of major cities now, and what I’ve found unique to Christchurch is that it’s a gridlocked city with a visible wealth divide between every single suburb. Again, there are reputations tied to the suburbs where you grow up."

This notion of schools and suburb status is further supported by the Christchurch City Council document, which discusses the concept of the "Christchurch elite." This long-standing influential group, concentrated in affluent suburbs like Fendalton, Merivale, and St Albans, has monopolised social and political power for years. Their children generally attend prestigious schools like Christ’s College and St Margaret’s, perpetuating an elitist reputation that has contributed to Christchurch’s conservative label.

So, while Christchurch's history is rich with progressive movements, the influence of controversies and certain powerful groups has shaped its reputation as a conservative city today. With this context in mind, let's explore the real experiences of people living in Christchurch.

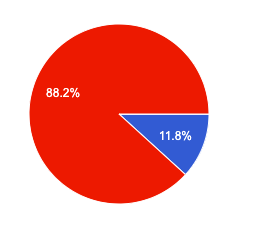

Have you ever been racially profiled or discriminated against on the basis of your race in Christchurch? [Red = no, blue = yes].

One respondent shared: "I’ve never felt particularly welcome or safe here; it’s just not a place that is accepting of anyone."

This sentiment was echoed throughout the survey, with many expressing that Ōtautahi lacks acceptance and diversity.

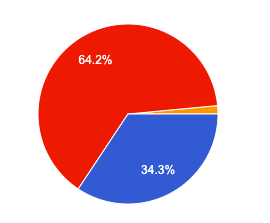

This notion is further reflected in individual responses to questions about discrimination - A significant 34.8% of respondents reported experiencing gender-based discrimination.

Have you ever been discriminated against on the basis of your gender in Christchurch? [Red = no, blue = yes].

One transgender respondent shared how they had "slurs yelled out of cars in town."

Another, a woman, revealed she had “been told to stay in the kitchen and [that] uni might not be the place for [her].” While transgender and female individuals were the most vocal about gender-based discrimination, some male respondents also shared their experiences, with one saying, “Male. Immediately being called a rapist or stalker or whatever.”

Multiple wahine also discussed the reoccurrence of catcalling, sexual harassment and other forms of abuse hurled at them by men, causing them to feel unsafe - even in public spaces.

Sexuality-based discrimination was reported by 20.9% of respondents, with many describing incidents ranging from disgusted looks to being verbally abused. One particularly harrowing account came from a respondent who shared that they were constantly harassed by friends in high school after coming out, to the point where they felt forced to "take it back" and claim they were straight. This experience left them terrified of exploring their sexuality, fearing that "everyone will hate me" if the truth came out. The lasting impact of this bullying has made them feel "gross" about not being straight.

Racial discrimination was reported by 11.9% of respondents, though the majority (88.1%) said they had not experienced it in Ōtautahi. Of those who did respond, one parent shared a distressing story: “My son is a person of colour, and he was first called the ‘n’ word when he was 3. The racism here is out of control.”

Another respondent, who is Middle Eastern, recounted experiences of being treated rudely by older supermarket staff, especially when compared to their white flatmate.

The results of our survey reveal that discrimination is a significant issue in Ōtautahi, contributing to its conservative label and impacting the lived experiences of many in the city.

Another person who is both Māori and Pākehā said I am white-passing, had a lady come up to me and ask me why I have a tā moko cause I'm white and I'm being racist. [I have h]ad people ask why Māori get free food and everything handed to them. [I have b]een told I'm only here cause I got a Māori scholarship. [I h]ave been told I'm not Māori enough. [I have h]ad people say outrageous comments about my race to my face, etc...”

As the results have shown, there are still a large number of UC students who haven't faced discrimination in some form - and as history also tells, conservativism might not be the right label.

Canta chats to Ōtautahi local, Tom Notton (they/them), after seeing a TikTok about his experience with racial profiling in town. After settling in Ōtautahi for the second year now, Notton has a good comparison of what it’s like to be a queer person of colour in four major cities. Dabbling in Auckland, Christchurch, Sydney, and Wellington - each one had its pits and its peaks. Growing up Cook Islands Māori and Aboriginal in Sydney presented fierce challenges involving bullying and racism, confronting Notton from the age of 8. But here in Ōtautahi, the past two years have presented fewer discrimination related challenges than expected.

“I guess it really depends on the circles that you surround yourself in. Because I experience nothing but acceptance generally. I'm not 100% sure why that is. I think I can safely assume that it is because I guess you gravitate to people to have the same values as you.”

Due to this gravitational pull, Notton doesn’t believe Ōtautahi is any more conservative than living in Wellington or Auckland.

From Notton’s perspective, queer culture in Ōtautahi “just looks different,” as the Queer community here puts in just as much effort as other major cities.

“I think that it's probably time for Ōtautahi to have that label taken off them. Just because to a certain extent, it does discredit a lot of queer people that do put in so much work."

Notton refers to permanently fixed queer bars and spaces in Wellington and Auckland, where the queer community will circulate those areas.

“That's amazing and great to have that safe space. But I find that here, we have an equal or near equal number of queer people that surround the city, but it's just more spread out.”

When hitting the town, Notton finds that his crew reside in Smash Palace or Flux, which are “not necessarily queer spaces”.

“We're just kind of spreading our queerness into little pockets that aren't specifically labelled. And I think that it's kind of a good thing in a way because it means that we're not just not just circling the same space and not interjecting ourselves into other communities. We're just kind of like, everywhere.”

In Auckland, Notton didn’t really experience the collision of both worlds, instead, “it was sort of like, there's the straights, there's the gays, you stay in your space. And that's it.”

Although Notton’s holistic view of Ōtautahi is generally a positive space for queer people, an experience Notton was subject to, sparked frustration in them.

While attending a New Regent street party early last year, Notton and their five friends were having a good time drinking and dancing. Other than their friend dropping a glass, and dancing “expressively”, Notton was just having a good time like everyone. Nothing significant occurred for attention to be drawn solely to Notton, but security from Gin Gin brought the fun to a halt when they accused Notton of being on drugs and kicked them out of an open street party.

“I honestly didn't even know what was going on. I don't think I've ever been targeted like that in Christchurch before. Or ever really. I don't go out a lot.”

Notton’s five Pākehā female friends were adamant Notton was the subject of racial profiling.

“And thinking back on it, it made me think, I was actually the only brown person there in general, not just in my group. Or within sight, at least.”

The night continued on, but the anger manifested in the morning, when Notton settled with the idea that they’d been racially profiled. Taking to TikTok to vent their frustration, Notton posted a video describing the situation, to which many people commented their agreement and experiences with being racially profiled in Ōtautahi. “Classic f*cken Christchurch,” said one commenter.

The real distaste sparked when Gin Gin viewed Notton’s Instagram story explaining the incident, choosing to ignore the allegations and divert from apologising.

“Because there was a lot of people from marginalised communities, people of colour, that were like, ‘oh my God, this happens to me all the time’.”

But also, Notton had Pākehā people telling him that the disposal of him from the street party might’ve been justified.

Besides boycotting Gin Gin due to the fact they didn’t apologise after viewing his concerns, the incident hasn’t affected Notton’s day to day life or comfort in the city.

Executive designer of QCanterbury this year, Aria Howes, was born and raised in the outskirts of central Ōtautahi, where representation and acceptance didn’t exist.

“It was always something that I hid growing up, I really found a community through online Instagram, social media stuff.”

Going to a tiny country school with only 120 kids enhanced the already difficult navigation of Howes' sexuality, as well as the pressures of generational religious values.

Finding a community at university and higher levels of support in the city appeared to be quite a culture shock, considering Howes' explanation of the homophobia in the Selwyn area.

“It's mostly when you reach the outskirts [of Ōtautahi]. You don't really see a lot of support.”

When asked about the homophobic values residing in Selwyn, Howes said, “[queer culture] is not necessarily spoken about, advocated for and people very much use slurs casually.”

While not witnessing the depths of homophobia firsthand, growing up in the country area highlighted the lack of education about the queer community.

“If you show any bit of anything opposite from the gender that you were signing up for, if you dress more masculine, when you're feminine, you get called a lesbian and stuff even, they just assume what you are. They don't really have an open mind about that sort of thing.”

Recognising that she wasn’t straight, Howes came to terms with her asexuality through supportive online spaces. Starting Rolleston High School in the first year group ever meant the stereotype moulds were scarce.

“I recognised that I wasn't straight, but it wasn't like the right environment to explore. There was hardly anyone in my year, so it was very much like you [had to] fit into the stereotypes of that area. Otherwise, you are an outcast. And so you’re kind of forced to fit in.”

A big push on education around queerness would be ideal for Howes, as figuring out your sexual identity is difficult, especially when navigating being asexual, which isn’t commonly discussed.

So, Howes has taken it into her own hands to study and enter the field of health to promote mental and physical well-being for queer people.

“I really want to give them a voice and different spaces. Definitely in a Rural area.”

Christchurch’s reputation as a conservative city is increasingly at odds with its complex reality. Historically a beacon of progressive change, the city now grapples with a blend of traditionalism and modern controversies. The perspectives of residents reveal a city where social advancement and discrimination intermingle, challenging simplistic labels. Rather than being defined by a single narrative, Christchurch emerges as a dynamic environment, where diverse experiences shape its identity and where the legacy of both progressivism and prejudice continues to evolve, for better or for worse.